The Commonwealth

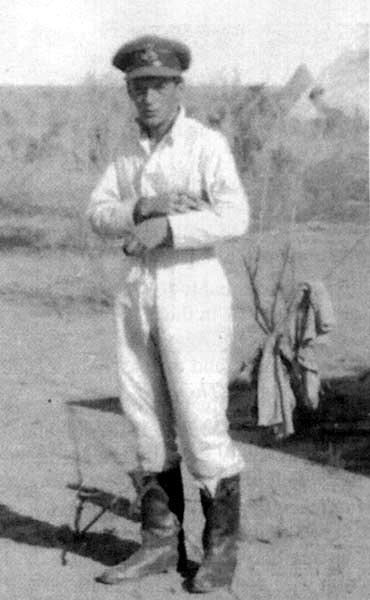

Air Commodore Percy Oliver Valentine Green, RAF no. 41015

The Commonwealth

Air Commodore Percy Oliver Valentine Green, RAF no. 41015

Oliver Green was born on 16 June 1920 in Purley, Surrey, and was educated at the Whitgift School in Croydon.

He joined the RAF in June 1938, undertaking initial flying training at 13 E & RFTS, following which he was awarded a short service commission on 20 August.

He completed his training at 11 FTS, Shawbury, in March 1939, then joining 3 Squadron at Kenley on Gladiators. As the airfield was being closed for enlargement, he was then posted to 54 Squadron, Hornchurch to fly Spitfires, but on 16 May 1939, he was posted to 112 Squadron when this unit was formed aboard HMS Argus in Portsmouth, Hampshire.

112 Squadron was sent to Egypt and arrived on 25 May 1939.

In June 1940, he served as Pilot Officer in ‘B’ Flight.

On 2 June, 'B' Flight moved to Sudan to form a 112 Squadron detachment here.

Between 06:00 and 07:40 on 31 July, Flying Officer Wittington (Gladiator K7986), Pilot Officer Chapman (L7916) and Pilot Officer Green (K7974) of 112 Squadron's Sudan Detachment flew an offensive patrol to Tessenei to search for three CR.42s reported newly arrived there but none were found. The airfield was machine-gunned and the patrol landed at Kashm El Gerba Landing Ground to refuel.

At 09:00, the patrol took off and returned to Gedaref at 09:20.

On 1 August 1940, Pilot Officer Green (Gladiator K7974) was scrambled at 08:10 from the polo field at Gedaref together with Flying Officer 'Dicky' Whittington (K7986) and Pilot Officer Hugh Chapman (L7619) after a single Caproni Ca.133 reported on reconnaissance over the area. Pilot Officer Green was first into the air and spotted the enemy aircraft almost immediately after taking off when it was about 500 feet above him at 1500 feet on his port beam. He chased it for 50 miles and managed to make an unobserved approach until dead astern. He delivered about twelve attacks and used some 1700 rounds before the bomber force-landed in a clearing with white smoke pouring from its starboard engine. One member of the Italian crew was seen to bale out.

Two members of the Italian crew were seen to climb out of the aircraft before Green set off back to Azaza where he landed 09:05.

The engagement lasted about 50 minutes and the Gladiator was hit by one round, fired from a window gun. Pilot Officer Green later described the combat:

"I saw a Caproni 133 bomber slipping through the scattered cloud at about 3,000 feet. I called the others on the R/T and set off in pursuit. My radio must have been faulty, which was not unusual, and they never heard me.Shortly after his return, a Valentia transport arrived and its pilot suggested that they go and try to find the surviving Italians, but after a while they returned empty handed. However, by this time Green had become something of a hero to the local populace that had been subjected to Italian bombing and so they killed a young goat for a feast in his honor!

I was soon involved in the exciting business of trying to catch the slow moving bomber whose skilful pilot weaved in and out of cloud hoping to throw me off. I was determined to get him and was able to close in and fire some long bursts which I could see hitting the aircraft but not doing any significant damage, even when they hit the engines.

Deciding to close in and see what was happening, I drew alongside only to find that the gunner was very much alive and well and aiming at me with his machine-gun. I felt a ping on my rudder bar and a sharp pain in my left knee.

He had fired one shot and then the gun stopped which was extremely lucky for me. I broke away sharply and came in right up behind and let him have a long burst. He started to go down, out of control, and parachutes billowed as those of the crew still alive bailed out.

The Caproni came down in a heap in scrub country and I saw two of the crew land and get rid of their parachutes. There was nothing further I could do so I took a brief note of the features of the landscape so I could report their location and set off back to the polo field.

There were no real landmarks such as rivers or roads so navigation was largely a matter of timing and gut feel. Finding the polo field again was quite difficult because we took off in such a hurry that I took no note of the time and had no accurate idea of how long I had been airborne. However, I found it, did a bit of a beat up and landed. Nobody knew I had been in action and they were astounded to hear that I had shot down the Caproni 133.

The ground crew were ecstatic and soon at work patching the bullet hole and checking the rudder bar and cables for damage. Dickey was a bit annoyed that he and Hugh had missed out but I said that they should have kept a sharper look out and, in any case, I had given all the correct calls over the R/T."

K7974/RT-O, which was used by Pilot Officer Green when he claimed a Ca.133 on 1 August 1940.

On 31 August 1940, he was transferred from 112 Squadron to the newly established 'K' Flight in Sudan, which was forming from the 112 Squadron detachment in Sudan.

At this time he was promoted to Flying Officer.

In the early afternoon of 21 November two S.79s raided Port Sudan. The cruiser HMS Carlisle opened fire and two Gladiators of 'K' Flight were scrambled to intercept. Flying Officer Green and Pilot Officer G. B. Smither attacked the bombers at 16000 feet, hitting both, but Green’s fighter was hit and damaged by return fire. The gunners in the S.79s claimed to have shot down both Gladiators.

Pilot Officer Smither (Gladiator K7948) only noted the interception in his logbook.

One S.79 was badly hit and returned with three wounded aboard. British radio interceptions led to the belief that the S.79 had force-landed at Karet, near Elghena, and Blenheim IVs of 14 Squadron were despatched to destroy it, but failed to find it there since it in fact had reached its home base in a damaged condition.

Smither later served in Burma where he was awarded a DFC and credited with a “Zero”. He was killed while serving in the RAF in 1953.

On 9 December, ‘K’ Flight at Port Sudan despatched six Gladiators Mk.IIs and one Mk.I, accompanied by a Wellesley carrying a fitter and a rigger, to Heliopolis to reinforce 112 Squadron during the upcoming Operation Compass. Flying Officer Green and Flying Officer R. B. Whittington of this Flight arrived at Sidi Hanaish from Heliopolis on 12 December while Flight Lieutenant John Scoular and Sergeant E. N. Woodward arrived on 16 December. At this later date, Flying Officer Jack Hamlyn had already been detached to 112 Squadron, flying his first known sortie on 13 December.

Subsequently ‘K’ Flight’ formed the basis of 250 Squadron, but on 8 May 1941, Green was posted as a Flight Lieutenant and flight commander to 73 Squadron in North Africa. This unit was at this time equipped with Hurricanes.

On 9 June, Flight Lieutenant Green led a section of Hurricanes on a strike to Gazala South (another section was to attack Gazala North). The operation was however hastily planned and executed. The Marylands, which were supposed to navigate for them, failed to rendezvous in the dark skies above Sid Haneish and Green decided to press on with his section alone to their target. They navigated the 200 miles in darkness with accuracy although one Hurricane had to return early. Arriving over the landing ground just as dawn was breaking, the three Hurricanes swept down for a strafing attack, machine-gunning a number of Bf 109s and G.50bis. Green observed six fires on the ground (a Fieseler Storch was also destroyed on Gazala South) as other Bf 109s scrambled to intercept while the airfield’s Flak but a warm welcome.

Green led the trio out to sea, but as he was doing so, he spotted a Bf 109 closing on the tail on Sergeant Bob Laing's Hurricane, at which he fired a burst and saw it dive away towards the sea. He then set course for Sidi Barrani, where he was the only of the three to return at 06:50.

Both Laing and 29-year-old Pilot Officer Greville Tovey (RAF no. 60315) were shot down by the Bf 109s of 1./JG 27 flown by Oberleutnant Wolfgang Redlich and Unteroffizier Günther Steinhausen, whom claimed victories at 05:00 and 05:05. Tovey was killed when Hurricane Z4118 crashed into the sea in flames but Laing survived when he made a forced-landing in Hurricane Z4429 within the Tobruk defence having been hit by Flak and then by a fighter. He was later rescued by Indian troops. Laing described his ordeal:

“We were ordered off early in the morning to fly 30 or 40 miles west to Gazala, to try and knock out any 109s we could find on the ground. It was not a good idea because it was just before dawn and you could not see enough to get yourself into position for a decent burst. I found two 109s but could not get a decent squirt at them although a Storch lit up nicely – not that it would bring the end of the war much closer! One of the Jerry ground gunners managed to hit my radiator; I felt a solid bang underneath which gave rise to a steady leak of steam and glycol, leaving a distinctive trail as I set off east. I was quite happy that I could at least reach Tobruk, but rather stupidly forgot that I made an excellent target against the dawn sky to which I was heading. I began to relax a little when I got a solid burst from a 109 up the tail, and I found it quite startling to hear the banging on the armour plate behind my seat, while the instruments on the top and sides of the panel disintegrated. I found myself thinking thank God that armour plating really works. Perhaps they were not using armour-piercing ammo. Some of the firing must have hit the control surface as the Hurricane grew steadily more nose-heavy. Just to add to my predicament the ether in the glycol was rising up from the floor and causing me to become anaesthetised. Anyway she hit the ground more or less level, with a bounce or two. My straps were none too tight and I banged my face on the gunsight, doing wonders to my natural beauty. She began to burn so I jumped out and started to walk a few miles towards Tobruk, feeling none too chipper. A small cave came into view and I laid down to recover a bit. I realised later that I had been concussed in the crash, and that I was not in any condition to do any steady thinking or walking. After an hour or two I was found by an Indian patrol and taken into Tobruk, and to hospital.”

On 15 June, 73 Squadron scrambled two sections when enemy air activity was reported. At 12:30, Green (Hurricane Z4697) and Pilot Officer ‘Robin’ Johnston (Hurricane V7802) encountered a Bf 110 over Sollum, presumably a reconnaissance aircraft from 2(H)/14. Both reported seeing their opening bursts hitting the Bf 110 as it dived away towards German lines, the Hurricanes meeting considerable AA fire, which damaged Green's Hurricane.

In the morning on 7 July, six Hurricanes from 73 Squadron took off, led by Flight Lieutenant Aidan Crawley, to strafe various airfields. First attacked was Sidi Aziez, but on leaving this location Flying Officer M. P. Wareham (Hurricane Z4773) noted that only three other aircraft were with him and that there were several columns of smoke rising from the Axis base. The four remaining pilots then attacked Gambut, but from here they encountered heavy Flak during their return journey. Wareham saw one Hurricane go down 15 miles east of Gambut, but when he landed he did so quite alone (his Hurricane was damaged by Flak). Flight Lieutenant Crawley (Hurricane V7802 - PoW) and Green (Hurricane Z4173 - PoW), Pilot Officers Stephen John Leach (Hurricane Z4649 - KIA) and Rodney William Kinkross White (Hurricane V7757 - KIA), and Sergeant Gordon Archibald Jupp (Hurricane M9197 - KIA) all failed to return. Oliver Green recalled what had happened:

“We positioned at Sidi Barrani, our forward refuelling strip, where we could also rendezvous with our top cover. Bill Smith was leading the 229 contingent so I felt assured of good support, particularly as I had won some money from him at poker the night before and I knew he was keen to get it back. Thie other squadrons were also there and they too off first so that they could climb to height and be in position. We went off in loose tactical formation, giving us freedom to manoeuvre and maintained tactical radio silence. Our course to Greater Gambut from Sidi Barrani was in a rough west-north-west direction and I was surprised that Aidan led us on a northerly course roughly parallel to the enemy coast, knowing that he would had to turn west towards Gambut and that he was increasing our chances of being spotted and reported by their listening post as we crossed the coast.Three casualties were recorded among Regia Aeronautica personnel at Gambut after the attack - a young car driver, killed, a fitter, Av.Sc Ugo Giacomazzi, and a pilot, Sergente Maggiore Francesco Visentin, both wounded. Also some G.50bis suffered minor damage.

Looking back on our ill-fated sortie, I realised that Aidan had not actually flown over enemy territory before. Nevertheless, it was surprising when he crossed right over the top of the coastal town of Bardia which was the main German garrison and forward base for their tank forces. We sailed over the town at 2,000 feet, just as if giving a flying demonstration. I knew that we were bound to have been spotted and reported to their fighter organisation and that our only hope lay in dropping to ground level immediately and flying south in the hope of gaining some tactical advantage before turning west for the attack on Gambut.

'The only way to do this was to break radio silence to tell him that I would lead him to the target at low level. To my consternation my radio set was not functioning. I could neither transmit nor receive. This was not an unusual fault and we normally overcame it by using hand signals but from my position on the right flank with another pair of aircraft between us, there was no way I could signal to him. I could only hope we would not be picked up and, if we were, that Bill and his boys could give us protection. However Aidan carried on at 2,000 feet before descending in a shallow dive on Lesser Gambut, the wrong airfield. Now surely, I thought, we must turn south and do a deep diversion before heading north for a very low level run from a different direction on the right airfield.

Aidan however had different ideas and climbed up slowly to 1,000 feet searching for Greater Gambut which lay about ten miles to the south. I should explain that airstrips in the desert were hard to pick up as they consisted of an area of level sand with no runways or buildings and only a few tents and refuelling bowsers. In short, they looked like any other stretch of sand. After doing a leisurely circuit Aidan saw Greater Gambut and went into another shallow dive attack. I had no option but to follow him although it was a recipe for disaster and compounded when I got my first glimpse of the target and saw there were no aircraft there. The birds had flown and our trip had been in vain. Just as I realised this I saw tracer bullets, looking like red ping pong balls, zipping past me. I immediately broke hard left, away from Rod [Pilot Officer R.W. K. White], who was close in on my right, and behind the formation hoping that he would be able to stick with me.

We were flying at ground level by then and although he turned with me, tragically he hit the ground and exploded in flames. The attacking formation was a mix of 109s, G.50s and what looked like Macchi 200s but I was too busy taking evasive action to look closely or even care for it was obvious that they had made me their principal target. My last sight of Aidan was of him sailing along with his boys apparently unaware of what was happening behind him. I knew that against these superior odds, my only chance of survival was to keep twisting and turning at ground level to make it as difficult as possible for them to get a clear shot at me and to keep heading for home. I could see the bullets hitting the ground alongside and ahead of me and knew I would have to be very lucky to get away.

Sure enough, after a short, desperate series of evasive turns the oil tank was hit and exploded. Oil sprayed all over the windscreen, effectively blinding me, and the engine seized and stopped with a bang. I hit the ground at about 180 mph and, although my straps were done up tightly, my snapped forward and hit the gyro gunsight with protruded from the windscreen. We rocketed along the ground. Bouncing about in a cloud of dust, my greates fear was that my Hurricane would burst into flames and I would be trapped inside.

My luck was in. As we came to a halt, I was able to scramble out and run from the wreckage before they strafed it and me. I got far enough away to be a spectator to their attacks. Curiously, the Hurricane did not burn, perhaps due to the recent fitted self-sealing tanks. After a short time and several attacks each, they flew away and I was left alone to contemplate that loneliest of all feelings, total isolation in the desert, one of the most unfriendly and harshest of place on earth. As I collected my thoughts and tried to work out what to do next, I heard the noise of an aircraft overhead and looked up to see a Blenheim flying home. There could not have been a more poignant reminder of my isolated predicament.”

He was held in Derna, Athens and Salonika, reaching Dulag Luft in Germany in August 1941.

He escaped from the hospital here, but was recaptured after a week of freedom.

After being held for nearly one year in Oflag VIB, Warburg, and then in Oflag 21 B at Schubin, Poland, until March 1943, when he was transferred to Stalag Luft III, Sagan.

In January 1945 the camp was evacuated ahead of the advancing Soviet army, and after a long trek Luckenwalde, 30 kilometres south of Berlin, was reached.

In April the camp was overrun by a Soviet tank division, and in early May he escaped from Soviet troops guarding the camp, who were proving hostile, and reached US forces at Magdeburg.

From here he was flown to Brussels, arriving back in England on 9 May 1945.

Here he was confirmed as a Squadron Leader with effect from August 1944.

Green ended the war with 1 biplane victory, this one being claimed while flying Gloster Gladiators.

In October 1945, he undertook training for Transport Command.

In June 1946, he joined 187 Squadron on Dakotas, and the following month commanded a detached flight of this unit in Italy, flying transport routes to British missions in Soviet-occupied Eastern Europe.

The flight here became 238 Squadron in October and moved to Schwechat, Austria, before returning to the UK in November 1947.

Here he became Ops 1 at HQ, 38 Group, until October 1948, receiving an AFC during the year.

He then became OC Flying and chief test pilot at Seletar, Singapore.

In December 1948, he took command of 110 Squadron at Changi, moving this Dakota-equipped unit to Seletar in June 1949.

The following month he moved to command 70 Squadron at Kabrit, Egypt, where in January 1950 the unit re-equipped with Valettas.

In May 1951, he returned to the UK to become involved in flight safety at HQ, Costal Command.

Promoted Wing Commander in January 1954, he became RAF Liaison on the staff of CINC Channel Command, NATO.

August 1956 saw a move to Ceylon to command RAF Negombo.

He returned again to the UK in May 1959 to attend the Flying College at Manby, flying Meteors, Hunters and Canberras, and in January 1960, newly-promoted Group Captain, he became commander of RAF Chivenor, home of 228 OCU, the Hunter training unit.

In September 1962, he was sent to South Australia as Senior RAF Officer at RAAF Edinburgh Field, dealing with weapons research and development.

He returned once more to England in January 1965 to attend the Imperial Defence College, and in February 1966 was promoted Air Commodore, becoming Commandant at the RAF Staff College, Andover.

August 1968 saw him as United Kingdom national military representative at Supreme HQ, Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE).

He became AOC Air Cadets and Commandant of the Air Training Corps in July 1971, but in November 1973 requested early retirement.

He was invited by the trustees of the Duke of Bedford to become managing director of a company formed to build and run the Woburn Golf and Country Club, being himself a great golfer.

In January 1985, having reached retirement age, he formed a leisure sports partnership, Green, Spier and Partners, and in January 1987 retired to Australia, where he still is living.

In 1999 he had an autobiography published, entitled Mezze; Little bites of flying, living and golfing (Ryan Publishing).

Claims:

| Kill no. | Date | Time | Number | Type | Result | Plane type | Serial no. | Locality | Unit |

| 1940 | |||||||||

| 1 | 01/08/40 | 08:30 - | 1 | Ca.133 | Destroyed | Gladiator | K7974 | Gedaref area | 112 Squadron |

| 21/11/40 | p.m. | ½ | S.79 | Shared damaged | Gladiator | Port Sudan area | ’K’ Flight | ||

| 21/11/40 | p.m. | ½ | S.79 | Shared damaged | Gladiator | Port Sudan area | ’K’ Flight | ||

| 1941 | |||||||||

| 09/06/41 | a.m. | 1/3 | Storch | Shared destroyed on the ground | Hurricane | Gazala South | 73 Squadron | ||

| 15/06/41 | 12:30 | 1/2 | Bf 110 (a) | Shared damaged | Hurricane | Z4697 | Sollum | 73 Squadron |

Sources:

A History of the Mediterranean Air War 1940-1945: Volume One – Christopher Shores and Giovanni Massimello with Russell Guest, 2012 Grub Street, London, ISBN 978-1908117076

Desert Prelude: Early clashes June-November 1940 - Håkan Gustavsson and Ludovico Slongo, 2010 MMP books, ISBN 978-83-89450-52-4

Dust Clouds in the Middle East - Christopher Shores, 1996 Grub Street, London, ISBN 1-898697-37-X

Fighters over the Desert - Christopher Shores and Hans Ring, 1969 Neville Spearman Limited, London

'Glad' brings down a bomber - Andrew Thomas, 2010 Flypast October 2010.

Hurricanes over Tobruk - Brian Cull with Don Minterne, 1999 Grub Street, London, ISBN 1-902304-11-X

Luftwaffe Claims Lists - Tony Wood

Shark Squadron - The history of 112 Squadron 1917-1975 - Robin Brown, 1994 Crécy Books, ISBN 0-947554-33-5

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Those Other Eagles – Christopher Shores, 2004 Grub Street, London, ISBN 1-904010-88-1

Additional information kindly provided by Graham Buxton Smither.