The Commonwealth

Group Captain Alan Charles Rawlinson OBE DFC and Bar AFC RAF, RAAF no. 386

The Commonwealth

Group Captain Alan Charles Rawlinson OBE DFC and Bar AFC RAF, RAAF no. 386

31 July 1918 – 28 August 2007

Born in Fremantle, Western Australia, on 31 July 1918, but subsequently a resident of Ivanhoe, Victoria,

He obtained a private pilots license in 1937 flying DH60 Gypsy Moths.

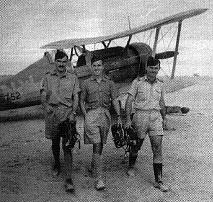

Enlisting in the RAAF in 1938 as an Air Cadet he graduated as a Pilot Officer in July 1939. He received a short service commission and was posted to 3 RAAF Squadron at Richmond, N.S.W. At the time the unit was flying Hawker Demons.

On 15 July 1940 3 RAAF Squadron embarked on RMS Orontes at Sydney for service overseas.

At this time the unit consisted of the following flying personnel:

Squadron Leader Ian McLachlan (CO).

“A” Flight:

Flight Lieutenant Gordon Steege (OC), Flying Officer Alan Gatward, Flying Officer Alan Boyd, Pilot Officer Peter Turnbull and Pilot Officer Wilfred Arthur.

“B” Flight:

Pilot Officer Charles Gaden (OC), Pilot Officer L. E. Knowles, Pilot Officer V. East, Flying Officer Rawlinson and Flying Officer B. L. Bracegirdle.

“C” Flight:

Squadron Leader P. R. Heath (OC), Flight Lieutenant Blake Pelly, Pilot Officer J. M. Davidson, Flying Officer John Perrin and Pilot Officer M D. Ellerton.

Totally the squadron had 21 officers and 271 of other ranks on 24 July.

On 7 August RMS Orontes arrived at Bombay and the unit was transhipped the same day to HT Dilwara.

HT Dilwara sailed on 11 August and arrived at Suez on 23 August where the squadron disembarked.

On 19 September, 3 RAAF Squadron received instructions from H.Q.M.E. that four pilots with nine ground crew were to be attached to 208 Squadron in the Western Desert for operational duties. The pilots detailed for this duty were Flight Lieutenant Blake Pelly and Flying Officers Rawlinson, Peter Turnbull and L. E. Knowles.

The pilots collected Gloster Gauntlets from 102 MU at Abu Sueir the same day and proceed to 208 Squadron the following day while the ground crew followed in a Bombay.

On 18 October, 3 RAAF Squadron had six Lysanders, 12 Gladiators and six Gauntlets.

The Gauntlets were on detached duty with 208 Squadron. The pilots on this duty were Flight Lieutenant Gordon Steege, Flight Lieutenant Blake Pelly, Flying Officer L. E. Knowles, Flying Officer Rawlinson, Flying Officer John Perrin and Flying Officer J. M. Davidson.

On 2 November 1940, squadron headquarters and ground personnel of ‘B’ and ‘C’ Flights of 3 RAAF Squadron moved by road from Helwan to Gerawla. The move started at 08:15 and was completed at 17:15 the next day.

Squadron Leader Ian McLachlan, Flying Officer Alan Gatward, Flying Officer M. D. Ellerton, Flying Officer Alan Boyd, Flight Lieutenant Charles Gaden, Flying Officer B. L. Bracegirdle, Flying Officer Peter Turnbull and Flying Officer Wilfred Arthur moved from Helwan to Gerawla by air on 3 November.

Flight Lieutenant Gordon Steege, Flight Lieutenant Blake Pelly and Flying Officer Rawlinson left their attachments to 208 Squadron and rejoined 3 RAAF Squadron at Gerawla while Flying Officer John Perrin, Flying Officer L. E. Knowles and Flying Officer J. M. Davidson, who also had been attached to 208 Squadron returned to ‘A’ Flight at Helwan.

15 Air gunner/Wireless operators from 3 RAAF Squadron were attached to 208 Squadron.

After the completion of these movements the disposition of the squadron was that at Gerawla there were:

Officers: 13 pilots, 1 crew, 6 non-flying and 2 (attached) air intelligence liaison.

Airmen: 185 non-flying, 6 (attached) air intelligence liaison and 1 (attached) Royal Corps Signalist.

Aircraft: 10 Gladiators and 4 Gauntlets (two Gauntlets had been left at 208 Squadron, Qasaba, being unserviceable and awaiting spares).

At Helwan (‘A’ Flight):

Officers: 3 pilots and 1 crew.

Airmen: 5 crews and 32 non-flying.

Aircraft: 6 Lysanders and 2 Gladiators (in reserve for ‘B’ and ‘C’ Flights).

Attached to 208 Squadron:

Officers: 2 crew.

Airmen: 5 crew and 15 non-flying.

Attached to 6 Squadron:

Airmen: 6 crew and 14 non-flying.

At Hospital:

2 airmen.

At Abu Sueir (on anti-gas course):

2 airmen.

After the capture of Sidi Barrani on 16 September, the Italian Army formed a defensive line composed of big outposts separated by wide desert areas. From north to south there were the 1a Divisione Libica (1st Libyan infantry division) at Maktila, near the sea east of Sidi Barrani and the 4a Divisione Camice Nere (4th Black shirts Division) at Sidi Barrani. South of these were the 2a Divisione Libica (2nd Libyan infantry division) in three strong points called Alam El Tummar East, Alam El Tummar West and Point 90 (also called Ras El Dai). South of this was the motorised ”Maletti Group” in the entrenched camp of Nibeiwa (strong points: Alam Nibeiwa and Alam El Iktufa). Then there was a gap of around thirty kilometres (called the Bir Enba gap) and at the extreme south of the Italian front the 63a Divisione di Fanteria (Italian Infantry division) ”Cirene” in four strong points around the rocky hill of Bir Sofafi; Alam El Rabia, the crossroads at height 236, the crossroads at Qabe el Mahdi and Height 226 at Bir Sofafi.

This deployment was clearly lacking, in particular, the worst error seemed the wide gap between ”Maletti” and ”Cirene” a distance that allowed for encirclement of the forces south of Sidi Barrani and north of Bir Sofafi.

On 19 November, General O’Connor ordered a fully motorised support group to enter the gap and stay there as to mark the British supremacy over the important area (in fact he had already planned to use this zone to pass through his troops and attack Nibeiwa). Reconnaissance units of the ”Maletti” Group signalled the dangerous presence of British armoured cars, and a combined action was planned for the day after.

During the early morning, a formation of 17 fighters of the 151o Gruppo escorted a formation of Bredas attacking enemy troops in the Bir Enba area and a Ro.37bis reconnoitring in the same general area. The mission was uneventful and the 366a Squadriglia went down after the Bredas to strafe enemy vehicles.

Then an armoured column of the ”Maletti” Group (420 troopers and 27 officers on 37 trucks with a strong of artillery of six anti-tank and six medium calibre guns and 27 M11/39 medium tanks) left Nibeiwa and a column of the 2a Divisione Libica (256 troopers and 17 officers on 29 trucks with four anti-tank and eight medium calibre guns) left Tummar. They had to rendezvous and then explore the Bir Enba gap. British forces opposing them are not known but Italian Intelligence estimated an armoured group of 60 to 70 tanks and armoured cars (the Italian Intelligence generally overestimated the actual force of the Commonwealth troops by a factor of between two to ten).

At 12:40, the ”Maletti” group was attacked by the British forces and forced to do battle. Around half an hour later at 13:00 the 2a Libyan’s contingent arrived and together they forced the British forces to retreat. While they were coming back to base, the British returned and attacked again, starting a dangerous rearguard action.

At 13:00, 18 CR.42s from the 13o Gruppo were ordered off from Gambut G to patrol the Bir Enba area. After take-off, a first group of 12 aircraft led by the newly promoted Tenente Colonnello Secondo Revetria stayed at 3000 meters while a second group of led by Tenente Guglielmo Chiarini covered them 2000 meters higher. Revetria’s formation included pilots from the 77a (Capitano Domenico Bevilacqua, Tenente Eduardo Sorvillo, Sottotenente Mario Nicoloso, Sergente Enrico Botti, Sergente Vincenzo Campolo and an unrecorded pilot), 78a (Sottotenente Natale Cima, Sergente Maggiore Salvatore Mechelli, Sergente Cassio Poggi and Sergente Teresio Martinoli) and 82a (Sottotenente Virgilio Vanzan) Squadriglie.

When they arrived over Bir Enba, Revetria made a first pass to better spot targets and observed an artillery duel between Italian guns and British tanks. Immediately the British vehicles, which were encircling the right flank of the Italian troops, stopped to fire and dispersed. Revetria and his eleven pilots attacked in single file causing a lot of damage among the enemies. After the strafing attack, the twelve 13o Gruppo pilots returned undamaged to base where they landed 14:50 after having spent 2200 rounds of 12,7 and 7,7 calibre ammunitions.

In the meantime, Chiarini’s formation was down to 4000 meters when they spotted a formation of a reported eight Gladiators that looked as they were trying to attack Revetria’s formation.

Chiarini immediately attacked with height advantage and surprised the Gladiator. The first pass only managed to break the Gladiator formation without causing losses and then a long dogfight started (Chiarini recorded that it lasted for 25 minutes) after which six British Gladiators were claimed shot down in flames, all shared by the six pilots of the Italian formation; Tenente Chiarini, Sottotenente Gilberto Cerofolini, Sottotenente Giuseppe Bottà, Sottotenente Giuseppe Timolina, Sergente Nino Campanini and Sergente Francesco Nanin. A seventh Gladiator was claimed as seriously damaged and was last seen flying low towards Matruh smoking and without taking evasive actions being claimed as a shared probable and the last Gladiator was also claimed as a shared probable. It was reported that all the victories were confirmed by the Libyan land forces (Chiarini also reported that the wreck of one of the Gladiators was noted on the ground by his pilots). The six Italian fighters came back almost without fuel left, they had used 1595 rounds 12,7 calibre and 2330 round 7,7 calibre ammunitions. Only four of them were slightly damaged. The heaviest damage was suffered by Timolina’s aircraft, which landed at an advanced airbase (probably Sollum) and was flown back to base the day after. His aircraft was still not operational at the beginning of Operation ”Compass” much more because of the inadequacy of the Italian repair organisation than because of the damage actually suffered.

It seems that the ”eight Gladiators” were in fact a formation of four Gladiators from 3 RAAF Squadron. Flight Lieutenant Blake Pelly (N5753), had been ordered to undertake a reconnaissance over enemy positions in the Sofafi-Rabia-Bir Enba areas. Squadron Leader Peter Ronald Heath (N5750), and Flying Officers Rawlinson (L9044) and Alan Boyd (N5752) provided his escort. The aircraft took off from Gerawla at 13:40. Flying at about 1,700 meters and with Pelly some 180 meters in front the escort, they headed for their objective. After about half an hour and about eleven kilometres east of Rabia, 18 CR.42s were spotted below strafing British troops. In accordance with orders, the reconnaissance flight turned around and headed for home. They had barely turned around when they were attacked by the CR.42s. Pelly out in the lead found himself at the centre of attention from nine Fiats. His escort were likewise engaged with a similar number.

Boyd found himself being attacked from astern by three aircraft. By twisting and diving he found himself behind one of them and fired off a long burst into the cockpit area. The Fiat rolled over and dived towards the ground. Pulling up into a tight turn he was able to bring his sights to bear on another enemy fighter. Coming in for a quarter attack, the Fiat fell into an uncontrollable spin with thick black smoke pouring from the engine. With barely a pause Boyd pulled round and went after a third fighter, which was attacking one of the Gladiators. After hitting it with a short burst it fell away. As he was watching it fall away, he was attacked from behind by yet another Fiat. Hauling hard back on the stick, he went straight up, with the engine on full power. This caused the enemy fighter to overshoot him. Rolling over, Boyd came down and fired directly into the engine and cockpit area, the Fiat then spun down towards the ground. Looking round, he saw another fighter and set off in pursuit. The Italian saw him and pulled up into a climb, Boyd followed but his engine stalled and he entered a spin, only pulling out when he was within 30 feet of the ground. As he pulled out, he was attacked by yet another Fiat. To complicate matters further Boyd’s guns had jammed, and he struggled with the mechanisms trying desperately to free them, all the while being pursued a few meters off the ground by an enemy fighter. At last, he freed up the two fuselage guns and in a desperate measure he yanked back the stick and went up into a loop. Coming over the top, he saw the Fiat below him and at a range of less than 30 meters he let fly with his remaining guns. The cockpit of the Fiat erupted with bullet strikes and it fell away to the desert floor.

With no more enemy aircraft in the vicinity, Boyd took stock of his situation. He had very little ammo left and only two working guns. In the distance, he saw one aircraft being pursued by two more. Turning in their direction he gained some altitude and closed in. He soon recognised Pelly’s Gladiator coming under attack from two Fiats. He immediately attacked one which was firing on Pelly, who was about to land with a faltering engine, this aircraft rolled over and dived towards the ground which was only 10 meters away. It seems unlikely that it could have pulled out. Pelly’s engine had picked up again and he started to climb away from the area. The remaining Fiat turned on Boyd, whose guns had jammed again and chased him at low level for about a mile before giving up and turning away. Boyd rejoined Pelly and both pilots made their way home. Along the way Pelly had to land at Minqar Qaim at 14:45 when his engine gave out. It was discovered that his oil tank had been hit and all the oil had drained out (the aircraft was flown back to Gerawla the next day). Boyd continued on his own back to base where he landed at 14:50.

During this combat was 26-year-old Squadron Leader Heath (RAAF no. 87) shot down in flames and killed. He was later buried beside his aircraft.

Boyd was credited with three CR.42s shot down and one probable, Pelly claimed one shot down and one damaged, while Rawlinson claimed a damaged.

Flying Officer Boyd reported:

”I was one of a formation of three Gladiators escorting another Gladiator doing a Tac. R. At approximately 1400 I sighted 6 to 9 CR.42’s flying about 200 ft.

[60 meters] in a North Westerly direction. We immediately turned east and had gone about a mile when about 6 CR.42’s attacked from above and behind and slightly on my starboard side.

We broke formation and attacked individually. A dog fight ensued, the enemy not remaining in formation after the initial attack. I made several attacks four of which were on separate aircraft and at a very close range varying from 20 to 50 yards [18-46 meters]. The first was a close quarter attack, the tracers could be seen hitting the area of the pilots cockpit and towards the engine. The CR.42 the[n] fell away into a spin apparently out of control and was last seen at about 200 feet [60 meters] still spinning.

The last three close attacks on three separate aircraft were delivered as a stern attack with the enemy climbing steeply so that I could see almost straight into their cockpits.

Each spun away after I had fired bursts which I could see hitting the enemy aircraft. No. 1 of the three really had no room to pull out of the spin, No. 2 I did not see crash but he seemed to be in an uncontrolled spin 200 feet [60 meters] from the ground.

I then saw two CR.42’s on the tail of a Gladiator, so I went to his aid, gained height, directed a point blank attack on one CR.42’s tail. I fired a long burst into him at a range of about 20 yards [18 meters] and he flicked over and disappeared under me only 100 feet [30 meters] from the ground. I did not see him hit because of the second CR.42 which was attacking me, and as my ammunition had run out, I was relieved to see him make off. As I looked around the only aircraft I could see were this one and F.Lt. Pelly’s. The time was then about 1430 hours.

My height at the commencement of the battle was about 5000 feet [1,500 meters] and after the first few minutes the battle continued under 1500 feet [460 meters].

In the early stages of the battle I was firing at long range but after the first five to seven minutes I only fired when at very close range.”

Flying Officer Rawlinson reported:

”It was first observed that 9 to 12 C.R.42’s were diving below us from the SOUTH to NORTH. Our formation was flying WEST. We then turned EAST and the above formation was out of sight to the NORTH.Rawlinson also wrote that no CR.42s were seen to hit the ground.

About one to two miles [1.6-3.2 kilometres] after turning, three aircraft were observed coming up from below and firing. Our formation and the reconnaissance Gladiator commenced individual attacking. Three more C.R.42’s were observed to join in.

In the fight about five attacks were made by me on C.R.42’s, they broke off by turning and diving.

One C.R.42 was attacked head on and shots from a good burst appeared to hit the aircraft. He turned overhead and dived, but could not be followed up due to further attacks.

One Gladiator was observed diving away from the fight with a C.R.42 behind. I was above, and dived on the C.R.42. About two bursts were fired at it when it dived and broke away. I followed the Gladiator, who started a right hand turn and hit the ground while diving and burst into flames. The fight was then about three to four miles [4.8-6.4 kilometres] to the NORTH WEST. I turned SOUTH WEST and climbed, and was heading WEST; about four aircraft were observed fighting low down. I then lost sight of them, waited near the area, but could not observe any aircraft, and came home.

Time of Gladiator crash was 1417 hours.”

”While proceeding on reconnaissance to SOFAFI area in company with an escort of 3 other Gladiators, I encountered two formations of C.R.42 aircraft, consisting of EIGHT and NINE respectively.After the war, Pelly also added that he was also shot at by his own escort during this hectic 25-minute battle. He also recalls being picked up by a Lysander and flown back to base.

The formation of EIGHT attacked my escort and the other formation cut me off and drove me southwards. The interception occurred at 1400 when I was 7 miles [11 kilometres] EAST of RABIA, and my escort were two miles [3.2 kilometres] N.E of me. I was at 4,000 feet [1,200 meters] and my escort at 5,000 feet [1,500 meters].

I could not get back to my escort, and the repeated attacks of the NINE C.R.42s forced me Southwards, and I worked Eastwards.

Shortly after the commencement of the battle I found myself meeting one E.A. head on at 50 feet [15 meters]. We both opened fire and he dived under me and crashed into the ground.

About 5 E.A. must have broken off, but at least 3 pursued me and attacked determinedly until 1425 when I worked Northwards and rejoined on of my escort (F/O A.H. Boyd). These three then broke off.

During the battle at approximately 1405 I turned at two E.A. who were attacking me from rear and got in one good burst. This aircraft issued black smoke, which increased in intensity until he finally broke away. I saw him flying away in a cloud of black smoke.”

At 09:15 on 26 December, eight Gladiators from 3 RAAF Squadron took off from the LG south-west of Sollum to escort a Lysander doing artillery reconnaissance over Bardia. The Lysander failed to appear. At approximately 14:05 (obviously during a third patrol) two flights of five SM 79s escorted by a number of CR.42s were observed a few miles north-east of Sollum Bay. A separate formation of 18 CR.42s was following the bomber formation and escort 2,000 feet higher as top cover. Two Gladiators attacked the bomber formation whilst the remainder climbed to meet the higher formation. The attack on the bombers was broken off when the higher formation attacked the Gladiators. In the ensuing combat, Flight Lieutenant Gordon Steege and Flying Officer Wilfred Arthur each claimed a destroyed (seen to fall into the sea) and a damaged CR.42. Flying Officer Peter Turnbull, Flying Officer John Perrin and Flying Officer Rawlinson each claimed one probable.

The CR.42s were 14 fighters from the newly arrived 23o Gruppo led by the CO, Maggiore Tito Falconi and 22 CR.42s from the 10o Gruppo. The CR.42s from the 23o Gruppo included three from the 70a Squadriglia (Tenente Claudio Solaro, Sergente Pardino Pardini and Tenente Gino Battaggion), five from the 74a Squadriglia (Capitano Guido Bobba, Tenente Lorenzo Lorenzoni, Sottotenente Sante Schiroli, Sergente Maggiore Raffaele Marzocca (forced to return early due to a sudden illness) and Sergente Manlio Tarantino) and five from the 75a Squadriglia (Tenente Pietro Calistri, Tenente Ezio Monti, Sottotenente Renato Villa, Sottotenente Leopoldo Marangoni and Maresciallo Carlo Dentis). The fighters from the the 10o Gruppo included seven from the 91a Squadriglia (Maggiore Carlo Romagnoli, Capitano Vincenzo Vanni, Capitano Mario Pluda, Sottotenente Andrea Dalla Pasqua, Sottotenente Ruggero Caporali, Sergente Maggiore Lorenzo Migliorato and Sergente Elio Miotto), nine from the 84a Squadriglia (Capitano Luigi Monti, Tenente Antonio Angeloni, Sottotenente Luigi Prati, Sottotenente Bruno Devoto, Sergente Domenico Santonocito, Sergente Corrado Patrizi, Sergente Piero Buttazzi, Sergente Luciano Perdoni and Sergente Mario Veronesi) and six from the 90a Squadriglia (Tenente Giovanni Guiducci, Tenente Franco Lucchini, Sottotenente Alessandro Rusconi, Sottotenente Neri De Benedetti, Sergente Luigi Contarini and Sergente Giovanni Battista Ceoletta), which had taken off at 13:00.

They were escorting ten SM 79s from the 41o Stormo under Tenente Colonnello Draghelli and five SM 79s 216a Squadriglia, 53o Gruppo, 34o Stormo, led by Tenente Stringa. The SM 79s had taken off from M2 at 12:25 and attacked Sollum harbour’s jetty (reportedly hit) and two destroyers inside Sollum Bay (with poor results because of the heavy AA fire). AA from the ships hit four bombers from the 34o Stormo; one of them, piloted by Sottotenente Bellini had to force land close to Ain El Gazala with the central engine out of action. Returning pilots reported an attempt to intercept by some Gladiators but the escort repulsed the British fighters. They landed without further problems at 15:15.

Over the target, immediately after the bombing, the Italian fighters reported the interception of “enemy aircraft” alternatively “many Glosters” or “Hurricanes and Glosters”. The 70a Squadrigli pilots claimed a shared Hurricane, this was possibly an aircraft from 33 Squadron. This unit’s ORB reported that during the day’s patrols many SM 79s and CR.42s were intercepted with one CR.42 believed damaged. Two Gladiators confirmed and two probables were shared between the whole 10o Gruppo. Another Gladiator was assigned to the 23o Gruppo (in the documents of 75a Squadriglia but this is not confirmed by the other two Squadriglie). Many Glosters were claimed damaged by Tenente Lorenzoni, Sottotenente Schiroli, Sergente Tarantino, Sottotenente Marangoni, Tenente Calistri, Tenente Monti and Sottotenente Villa. The CR.42s were back between 14:30 and 15:05.

No Gladiators were lost even if three of them were damaged (all repairable within the unit). The Australians had done a very good job indeed, facing a formation four times more numerous (even if it seem improbable that all the Italian fighters were able to join the combat). From the Italian reports it seems that only the front sections of the escort (including the 74a, 75a and the 84a Squadriglie) were engaged in a sharp dogfight with the Gladiators. The Australians were able to shot down the CO of the 74a Squadriglia, Capitano Guido Bobba, who was killed when his fighter fell in flames into the sea and damaged Tenente Lorenzoni’s fighter, who landed at T2 (and came back to Z1 the day after). Three more CR.42s were damaged when Tenente Angeloni was forced to land at T5 before reaching Z1, Sergente Veronesi’s fighter was damaged and Sottotenente Prati was forced to make an emergency landing short of T2 (his fighter was reportedly undamaged and only suffering for a slight engine breakdown). Maggiore Falconi’s fighter was also heavily damaged but managed to return. The morning after Angeloni was able to return to Z1 with his aircraft.

Capitano Guido Bobba was awarded a posthumously Medaglia d’Argento al valor militare. He was replaced as CO of the 74a Squadriglia by Tenente Mario Pinna.

On 22 January 1941, Flying Officers Rawlinson (Gladiator K7963) and Wilfred Arthur (L8009) took off at 10:20 and attacked a stationary schooner in the sea, 13 miles north of Tobruk. They landed back at 11:10. The schooner was later reported on fire.

On 25 January, four Gladiators of 3 RAAF Squadron flown by Flight Lieutenant D. Campbell (N5857), Flight Lieutenant Rawlinson (K7963), Flying Officer Peter Turnbull (L9044) and Pilot Officer J. C. Campbell (K8022) took off from Tmini at 07:30 to carry out a protective patrol over the Armoured Brigades operating in the Mechili area. Whilst flying at 600m, 13km south-east of Mechili, five G.50s, which were flying at 3000m, attacked and broke the Gladiators formation. During the combat, 22-year-old Pilot Officer James Chippindall Campbell (RAAF no. 634) was shot down and killed, while Flight Lieutenant Campbell was forced to make an emergency landing in the desert and the other two biplanes were damaged. Flying Officer Turnbull recalled:

”My position in the flight was astern of the Vic. Formation acting as swinger when E/A. was first sighted. The formation immediately turned east and we were over our advanced troops when first attacked by E/A. Each time I was attacked from astern and above and to avoid being hit, I made a side-slipping turn back underneath. As the E/A passed overhead, it made a climbing turn to the left, and I was able to get well within range by turning right. I was attacked nine times and each time I carried out the above avoiding action, but three of my guns ceased to fire owing to stoppages during the first attack and the fourth after the fifth attack. Could see bullets hitting E/A during the third, fourth and fifth attacks, which were at close range.Rawlinson claimed two more G.50s damaged. These three claims for damaged aircraft are, however, not officially credited in the unit’s ORB.

The E/A appeared to be similar to that of a Breda 65 but the pilots cockpit was well back near the trailing edge of main planes. This being the only outstanding point which could be seen at the time. They were very fast, and by the dust made by their fire on the ground, they appeared to be armed with two.5’s."

”We first noticed the enemy while we were proceeding west about 8 miles South East of Mechili. We were at 2000’ and they were at approx. 10 000’ and on the port forward quarter.The Gladiators were all back at Tmimi by 08:45.

I turned the formation to the east and the enemy immediately gave chase. They made a stern attack from above, breaking up our formation. I received a bullet through the starboard upper mainplane while turning away. I then made a quarter attack and received another burst from behind through my elevator.

I then found that I was to one side of the engagement which consisted of two gladiators and two enemy machines. While moving across to join the other two I was again attacked from astern and above, the centre section being hit. I forced landed at the same spot and watched three enemy machines proceeding Westward. After making an inspection of my machine I flew back to TMIMI. The ammunition used by the enemy was.5” explosive bullets. They were radial engine, low wing monoplanes with no well defined hump on the pilot’s cockpit. At first however we thought they were Hurricanes since we had expected Hurricanes to be patrolling the area and the silhouette was similar.”

On 27 January, many pilots of 3 RAAF Squadron were promoted. Squadron Leader Ian McLachlan was promoted to temporary Wing Commander, Flight Lieutenant D. Campbell and Flight Lieutenant P. Jeffrey was promoted to temporary Squadron Leaders while Flying Officers John Perrin and Rawlinson was promoted to temporary Flight Commanders.

In March 1941, Rawlinson was loaned to 6 Squadron for reconnaissance duties.

On 5 March he was slightly injured near Mersa el-Brega when his Hurricane (V7484) force-landed after engine failure.

Rawlinson later returned to 3 RAAF Squadron

Shortly after lunch on 3 April during the retreat at the end of the first Libyan Campaign, seven Hurricanes of 3 RAAF Squadron - now operating from a landing ground at Got es Sultan about 20 miles north-east of Benina, to where it had hurriedly withdrawn the previous night - accompanied by ‘B’ Flight of 73 Squadron, encountered eight Ju 87s of II./StG 2 about 15 miles south of Sceleidima, escorted by an equal number of Bf 110s of 7./ZG 26 led by the newly appointed Staffelkapitän, Hauptmann Georg Christl. The Stukas had been attacking British troops near Derna.

One section of RAAF Hurricanes led by Flight Lieutenant Rawlinson (Hurricane V7772) and including Lieutenant G. K. Smith (P3980) and Flying Officer Jimmy Davidson (V7566) waded into the divebombers while Flight Lieutenant Gordon Steege's (P3937/OS-B) section, which included Flying Officer J. H. Jackson (V7770), Flying Officer John Saunders (V6737) and Flying Officer Peter Turnbull (V7492), engaged the escort. ‘B’ Flight of 73 Squadron did not become involved in this combat.

Flying Officer Jackson's journal provides an account of the ensuing series of engagements:

"About noon we went off on another patrol, about ten of us. We now have four or five pilots from 73 Squadron attached to us. We need them too, as some of our chaps are very war-weary and showing the effects of the strain. We got no distance south of Sceleidima when somebody spotted enemy aircraft. We were in three flights, Gordon Steege leading bottom flight with myself, John Saunders and Pete Turnbull, Alan Rawlinson leading middle flight about 1,000 feet above us, and a flight of 73 Squadron above them. The top flight did a wild goose chase after one of our Blenheims they spotted out on our starboard side, which happened to be returning from a reconnaissance, and they did not see the enemy which turned out to be about ten ME110s escorting about 15 Ju87s, which were dive-bombing and ground strafing our retreating ground forces. I only spotted two ME110s and didn't see any of the other enemy aircraft. I followed Gordon Steege into attack and got on the tail of a ME110, just after he had fired a few rounds at it and sheered away from it. I fired two bursts then my guns stopped – rotten luck. Just as I was getting in close, I saw a few bits and pieces and sparks flying from the ME110. Pete Turnbull followed me in on the same ME110 and gave it a burst also. Gordon Steege got credit for this kite as he attacked first and probably got in the best attack. Immediately my guns stopped I did a steep spiral to gain speed and went like hell to get out of the area as it was useless to remain without guns firing. I flew back to Benina, where I knew the CO was still waiting, and gave him news of the fight.Totally in this combat 3 RAAF Squadron claimed 5 destroyed and 3 damaged Bf 110s and 4 destroyed, 2 probables and 2 damaged Ju 87s. Steege claimed 1 destroyed and 3 damaged Bf110s, Turnbull claimed 2 destroyed and 2 probable Bf110s (these were later upgraded to 4 destroyed), Saunders claimed 1 damaged Ju 87, Rawlinson claimed 2 destroyed, 1 probable and 1 damaged Ju 87s, Davidson and Smith claimed 1 destroyed Ju 87 each while Jackson claimed a probable Ju 87.

Pete Turnbull had a go at two more ME110s and blew an engine out of one and bits off another, and fired at a couple of others. Smithy, one of the three South African pilots attached to us, attacked the Ju87s and blew the tail clean off one and sent it down in flames. Jimmy Davidson also claimed a Ju87 and Alan Rawlinson sent two 87s down in flames. Wish my guns hadn’t stopped, I was feeling very fit and enjoyed the bit I had. I’m satisfied ME110s are no match for a Hurricane – at low heights we can catch them and out-turn them without too much trouble. All our chaps returned safely to Sultan through some had bullet holes - both Pete Turnbull and Jimmy Davidson had holes through their ailerons and both were jamming badly – they were very fortunate to get back. Pete also had a bullet through one of his tyres and landed nicely with one flat tyre. Three ME110s and five Ju87s, about five of them down in flames, and possibly others damaged.”

At 14:05 on 7 April 1941, Flying Officer Scott and Sergeant Alfred Marshall (Hurricane V7560/TP-F) of 73 Squadron took off, joining Flight Lieutenant Rawlinson and Flying Officer Lindsey Knowles of 3 RAAF Squadron on a patrol. A pair of Ju 52/3ms of III./KGrzbV 1 were seen on the ground about ten miles south of Mechili, and were strafed. Marshall claimed to have destroyed both, but the two Australian pilots also each claimed one destroyed. Marshall’s Hurricane was hit by ground fire but he managed to return. Knowles, however, was obliged to land at Gazala due to lack of fuel. Everyone was leaving, and on advice of the retreating troops, he set fire to P3980 and departed with them. When a truckload of volunteers from the squadron arrived to deal with the problem, it was only to find the burnt-out Hurricane and no sign of the pilot.

After the unit had converted to Tomahawks, he was involved in the Syrian Campaign.

On 19 June ten of Flotille 4F's Martin M-167Fs were off in two groups to attack the Australians around Sidon at 16:05, while seven Tomahawks of 3 RAAF Squadron escorted Blenheims on a leaflet raid over Masbaja and Merjayoun. Having seen their charges safely back into Allied territory, the Australians were ordered to the Sidon area, where four bombers of Escadrille 7B and three of 6B were seen and attacked, four being claimed damaged. Lieutenant de Vaisseau De Gail's 7B-3 at the rear of the formation suffered severe damage, while Ensigne de Vaisseau Lacoste was unwise enough to leave the formation when his 6B-6 was hit. Fortunately for him, the Tomahawks were by now low on fuel, and departed for their base without pressing the attack further.

It is most probable that three of the four damaged that were claimed were claimed by Flight Lieutenant Rawlinson (two damaged) and Flying Officer Peter Turnbull (one damaged) since both claimed damaged M-167s on this day.

On 28 June nine 3 RAAF Squadron Tomahawks led by Flight Lieutenant Rawlinson flew up to Damascus-Mezze where they refuelled, taking off again at 10:15 to escort Blenheims on a raid. At 10:10 meanwhile, six Martin M-167Fs of Flotille 4F had taken off, one section of two being sent to bomb troops south-east of Palmyra, while the other four as a second section headed for a British concentration near Mohammed Ben Ali, to the north of the oasis. The sections were:

1st section:

7B-5 (No 274) Ensigne de Vaisseau Massicot (pilot), Lieutenant de Vaisseau Lainé (observer)

7B-4 Osserver Engineur Le Friant

2nd section:

6B-3 Lieutenant de Vaisseau Ziegler

6B-4 Ensigne de Vaisseau Playe

6B-6 Ensigne de Vaisseau Lacoste

7B-6 (No 31) Lieutenant de Vaisseau De Gail, Premier Maître Sarrotte (pilot), Sous Maître Gueret

The Blenheims having completed their attack, the Australian's attention was caught by the explosions of bombs dropped by the Aeronavale aircraft, all six being seen bombing in pairs. In the execution, which followed, all the bombers were shot down, 6B-3, 6B-4, 6B-6 and 7B-4 all crashing with total loss of life. Premier Maître Sarrotte, the pilot of 7B-6, held the aircraft in the air long enough for the crew to bale out, he and Sous Maître Gueret surviving. From 7B-5, Lieutenant de Vaisseau Lainé and Ensigne de Vaisseau Massicot survived, though both were badly injured. They were found by Bedouins and carried to T-4 next day. Six officers and 14 airmen had died.

The Tomahawks returned to Damascus without damage, victories being credited to Rawlinson (three), Flying Officer Peter Turnbull (two) and Sergeant Wilson.

On 22 August Rawlinson had a freak accident with Tomahawk AM386 (‘SWEET FA’) when its starboard tailplane detached and it was only by great skill that he managed to land the fighter safely.

The unit returned to Egypt in September and he was awarded a DFC on 10 October. He was then posted to 71 OTU in the Sudan as an instructor. A month later he was recalled to 3 RAAF Squadron to take command, seeing considerable action during the 'Crusader' operation of that month.

At 09:45 on 22 November, twelve Tomahawks of 3 RAAF Squadron took off to escort Blenheims of 45 Squadron on a raid on the Acroma-El Adem road. The Tomahawks were subdivided into two groups of six, the first were formed as close cover, and three per side of the Blenheims, the second was placed as top cover with three pairs of aircraft. Flying Officer Bobby Gibbes recorded:

“I was on the morning operation in which B flight was to escort six Blenheims to bomb Bir el Gubi. After take-off we rendezvoused with five Blenheims instead of the expected six. We split into two sixes close cover, flying three aircraft on either side of the bombers. I flew in number one position on the port.The Australian fighters were back at base by 11:10. They claimed two probable (Sergeant Derek Scott in AN305 claimed both) and five damaged; Squadron Leader Rawlinson (AN406) and Flight Lieutenant Wilfred Arthur (AN389) one each of these – the other three were claimed by unknown pilots. Initially two pilots were missing and one killed but in the end all three were KIA; 22-year-old Pilot Officer Eric Hall Lane (AM378) (RAAF no. 406002), 21-year-old Flight Lieutenant John Henry William Saunders (AN416) (RAAF no. 471) and 28-year-old Flying Officer Malcolm Hector Watson (AK510) (RAAF no. 845).

The Blenheims were very much slower than our Tomahawks and we had to weave in order to stay alongside them. This actually was advantageous as it enabled us to scan the skies well, in search of enemy aircraft. We had arranged with the bomber crews for their rear gunners to fire into the air above if they saw enemy aircraft, and this would alert us if we hadn’t already spotted them. Our radio frequencies were different to those which the bomber radios were tuned to, and this was always a great disadvantage to all pilots and crews.

On the way to the target area, we passed a few miles to the port of enemy aircraft which were busily bombing our troop positions, with their fighter escort weaving above. We passed without much apparent notice of each other, as both lots of protective fighters were obliged to remain with their charges.

Shortly before reaching our target, a line of single black ack-ack bursts was seen above the broken cloud layer, and these, we knew, were to indicate to the German fighter pilots our position and heading. A few minutes later, a force of about 15 109s appeared above, and this formation split into two sections and started to attack our top cover. The top cover was free to mix it with the enemy, but we pilots giving close cover were obliged to remain with our five Blenheims.

Our top six did a wonderful, but terribly costly job in engaging the enemy and preventing them from attacking the Blenheims. Only two got through in an attempt to attack the bombers, and only one of these actually fired a quick burst at one of the rear aircraft. Two of us attacked it, driving it off. I was able to get into a very close position behind it, and only broke off my attack when I was in danger of running through the curtain of fire from the rear gunners of the bomber formation. I know that I was hitting it and I doubt if it did any real damage to the bomber, nor was I able to claim having damaged it as I did not see any bits fly off.

A second 109 dived onto the tail of my number three, Malcolm Watson. I saw it coming and 1 called a desperate warning to him, but again, our poor radio communication resulted in him not hearing me and he continued his weave. It hit him hard, and he half rolled, and went into a lazy spiral dive, evidently having been killed in the attack. I pulled around onto the 109 and fired at it as it dived away, but whether I damaged it or not, I do not know.

On two or three occasions during the combat, I felt my aircraft being hit and the strong smell of cordite permeated the cockpit. Each time my heart nearly stopped as I hadn’t seen an attacking aircraft. I took wild evasive action, but could not see the aircraft which had hit me. After suffering terrific fear on each occasion, I suddenly realized that I had been firing my own guns, and the point fives, being in the cockpit, accounted for the vibration and the smell of gunpowder. It was the first time that I had worn gloves when flying, and I wasn’t conscious that, without the normal feel of my finger on the trigger, I had been tensing my grip without being aware of doing so. I threw the gloves onto the floor of the cockpit and never wore them again.

The fighters up above slowly disappeared behind us and the plumes of dense black smoke from the desert below, bore mute testimony to the gallant action of our top cover. How many of the fires were enemy, and how many ours, we didn’t know. The bombers had done a good job. They ran up steadily on their target and dropped their bombs, I believe with great accuracy but unseen by us. It was enough for us to see the bombs leave their aircraft and to see them turn for home, while we wondered the while if we would ever make it. How slow those bombers were, and how slowly the desert passed below! How we wished that we could open our throttles and dive for home and safety, but this could not be! After landing back with our five bombers intact, our remaining top cover landed. We had lost three of our pilots, Malcolm Watson who I saw go down, and Johnny Saunders and Eric Lane. The three were killed. I have told how Malcolm went and later I learned that Eric Lane had been seen battling with three 109s. He got on the tail of one of these and had it smoking badly when another 109 jumped him from behind and shot him down in a mass of flames.

We never did hear how Johnny died.”

At 15:40 on 22 November, nine Tomahawks from 112 Squadron (led by Flight Lieutenant Gerald Westenra) and 13 from 3 RAAF Squadron led by Wing Commander Peter Jeffrey (CO 258 Wing in Tomahawk AN244 from 3 RAAF Squadron) took off for an offensive sweep over the Tobruk-El Adem area. With them were Wing Commander Fred Rosier (262 Wing) in a Hurricane II, who was planned to land in Tobruk during the return from the sweep.

At 16:15, south-east of El Adem a reported 15-20 Bf 109Fs were encountered at 11 o’clock at an altitude of between 4000 and 5000 feet and a furious battle ensued (112 Squadron also reported G.50s but this seems false since not Italian units is reported to have taken part in this combat).

For the first 15 minutes it was a free-for-all which gradually separated into individual dog-fights. Finally eleven Tomahawks formed a defensive circle with the Germans in a similar position, but slightly above. The circles flew round and round while every now and then an aircraft, seeing an advantage, would slip out and attack. While this was going on the enemy ground troops kept up a continuous fire of small arms and flak. In effect deadlock ensued, despite the Germans superiority in every respect but there was nothing he could do to force the issue. The fight lasted over an hour, and ended up, as night fell, with the Bf 109s flying off (with the height advantage they had all the initiative).

When 112 Squadron returned at17:20, the Tomahawks were short of fuel and landed all over the place, Pilot Officer John Bartle being the only one to reach LG 122. They claimed two victories when Pilot Officer Neville Duke (AK402/F) destroyed a Bf l09 south of El Adem at 16:15 after giving it a long burst at 100 yards. The hood and pieces of the fuselage falling off and the pilot, wearing a field-grey uniform, baled out. Pilot Officer John Bartle (AK538) managed a sustained burst with all his guns on another Bf l09F, killing the pilot over El Adem between 16:15 and 17:20. Their only loss was Sergeant H. G. Burney (AM390) who was shot down while three planes were badly damaged and three others slightly.

“…bound for Tobruk were attacked by 15/20 Me.109F’s from about 1000 feet above at 16.15 hours SE of El Adem. A dogfight ensued resulting in heavy damage on both sides. It is difficult to form a true picture of the battle which moved at great speed for the better part of an hour. For the first 15 minutes it was a free for all, gradually separating into individual dogfights from which our own and enemy planes began to break away one or two at a time. Finally 11 Tomahawks of both Squadrons formed a defensive circle 500 feet above the ground, with 6 Me.109’s 1000 feet above watching for possible stragglers. The 109’s made repeated dives on the outside of the circle which were immediately countered by the machines following the one attacked, pulling out to give the enemy a send off, and these on the opposing side lifting nose to meet the attack. This proved successful and the enemy eventually broke off and made for home…”Pilot Officer Sands observed:

“Pilot baling out of machine shot up by P. O. Duke.Pilot Officer Duke recorded:

A 109 burst into flames after a stern attack by an unidentified Tomahawk.

A 109 with pieces flying off and spinning in with wheels flapping and piece off wing after an assumed collision with a Tomahawk which had its wing shot off in this attack. FO Humphrey saw this machine crash.

2 Me. 109F destroyed…However, as at least six pilots made attacks on passing 109’s they must have suffered further unobserved damage.

Comments.

1. Smoke trails from enemy guns seemed to indicate a high percentage of tracers or incendiary bullets.

2. Camouflage- desert, with blue underneath and black crosses under wings and on fuselage with white edgings.

3. At least one G.50 was seen with a black cross on fuselage… [It seems unlikely that there were G.50s.]”

“One Me. 109 destroyed, own machine undamaged. Pilot baled out after long burst from 100 yards. Stern quarter. Hood and pieces of fuselage disintegrated. Pilot had on German Field Grey Uniform. Unable to strafe pilot owing to presence of other E/A.”It seems that Duke felt the need to justify himself for not having tried to kill the German pilot; this would make one think that there were orders to do precisely that, perhaps limited to when one was over enemy territory. After the war, Duke wrote:

“I got on the tail of one and followed him up. Got in a burst from stern quarter and its hood and pieces of fuselage disintegrated. Machine went into a vertical dive and the pilot baled out. Flew round and round the pilot until he landed, then went down to look at him. I waved to him and he waved back. Poor devil thought I was going to strafe him as he initially dived behind a bush and lay flat.Wing Commander Rosier landed beside Sergeant Burney to try to pick him up. The Hurricane burst a tyre on take-off and they had to abandon it. Enemy armoured cars were nearby so the two men had to hike 30 miles back to our lines where they were picked up none the worse for wear by the Indian Division. Wing Commander Rosier himself recorded later:

Rejoined Squadron which was going round and round in a defensive circle. The 109s kept diving down on us and I saw a Tomahawk go in with half its wing off after colliding with a 109. The fight lasted about 40 minutes. Longest ever! Force-landed after breaking away from circle by myself, at an advanced landing ground (LG. 134).”

“…I decided to fly to the besieged fortress of Tobruk to organise the airfield facilities for fighter operations and to find out why the post (radar) there was failing to give us early warning of the approach of aircraft from the west.The combat hit 3 RAAF Squadron harder and only Squadron Leader Rawlinson (AN365) landed back at LG 122 at 17:15 while five others (including Flight Lieutenant Wilfred Arthur in AN389) landed at LG 134 at 17:45 (one with starboard mainplane damaged). Two Tomahawks had returned earlier (both with magneto trouble) but six fighters were missing! Wing Commander Jeffrey was forced to land, but was picked up by Commonwealth troops uninjured and returned to 3 RAAF Squadron on 24 November while Sergeant Ronald Simes (AM507) was picked up by the 4th Hussars and returned to the Squadron on 26 November. Flying Officer H. G. H. Roberts in AN373 and Flying Officer W. G. Kloster in AK390 were both taken PoW while 24-years-old Flight Lieutenant Lindsay Eric Shaw Knowles (RAAF No. 456) in AN410 and 27-years-old Pilot Officer Lawton Lees (RAAF No. 400092) in AN305 both were KIA. In return, the Australians claimed three destroyed Bf 109s, one probable and eight damaged; Squadron Leader Rawlinson claimed two destroyed and two damaged, Flight Lieutenant Arthur claimed three damaged, Sergeant Simes claimed one destroyed, Flying Officer Robert Gibbes claimed one probable, Flying Officer Edward Jackson (AN441) claimed one damaged and Flying Officer Thomas Trimble (AK382) claimed two damaged. Flying Officer Gibbes of 3 RAAF Squadron recorded:

That afternoon with an escort of two Tomahawk squadrons, 112 (Shark) Squadron and 3 Squadron of the Royal Australian Air Force, I set off in my Hurricane II for Tobruk. We were well on the way when at 1615 hrs, south-east of El Adem, we were intercepted by a group of perhaps 20 Bf 109s. Bobby Gibbes wrote in his diary that day: ‘They straight away climbed up into the sun and came down onto us and started to dogfight. Soon got sick of that and formed a big circle about 2,000 feet above us and came down in twos and threes from all directions.’

After about 20 minutes, on breaking away, I saw a Tomahawk of 112 Squadron, diving down streaming smoke. I followed it down. He lowered his undercarriage and force-landed, only a few miles away from an enemy column which I had noticed. In order to prevent the pilot falling into the ‘bag’ I decided to attempt to rescue him. I landed the Hurricane alongside the Tomahawk and the pilot. Sgt Burney, an Australian, ran across to me. I jumped out, discarded my parachute and he climbed into my cockpit. I sat on top of him, opened the throttle and started to take off. Then disaster struck, just as I started my take-off run my right tyre burst. I accelerated but the wheel dug into the sand and we ground to a halt. There was nothing to do but abandon the plane.

At that time it was nearly dusk and, as there was an Italian armoured column about two miles away, we ran to the shelter of a nearby wadi. After some time as there was no sign of the enemy, we returned to the aircraft and I quickly removed all my possessions from the Hurricane, including my wife’s photograph…and hid them under some nearby brushwood. Taking some food and water we returned to our hiding place where we planned to spend the night. A little later, trucks arrived and Italian soldiers began to search for us. They found all my possessions but although they came within yards of where we were hiding behind some rocks, they did not see us.

The next morning, anxious to get as far away as possible from the scene of our landings, we set off in an easterly direction to walk the 30 miles or so back to our lines. That night, using the Pole star to navigate, we found ourselves in the middle of some German tanks and lorries. We started crawling on our hands and knees and I thought the game was up when lights came on and we were twice challenged by sentries. Eventually, when all became quiet we continued walking. As dawn was breaking we found ourselves still close to the enemy force who were searching for us on motorcycles. We therefore made for the shelter of some brushwood surrounding a dry well which was the only bit of cover for miles around.

At about 0800 that morning (24 November) we found ourselves in the middle of an artillery battle with shells falling on and around the enemy force close to us, which immediately began to disperse and withdraw. We then heard unmistakable orders being barked out in English. I decided that the best thing to do was to make a dash for it, so we ran until we eventually reached the artillery unit. We were at first greeted with suspicion but we were soon given some tea and food and sent on to an armoured brigade headquarters not far away.

They welcomed us and provided us with a truck and driver to take us to Fort Maddalena. En-route, as we approached a South African armoured car unit, shells started falling around us and a number of enemy tanks coming straight towards us appeared about two miles away The enemy force which we had encountered had broken through and was heading east towards the Egyptian frontier. The South African major’s last words to us were. ‘I think we are the last line of defence before the wire.’ So we turned round and went like the wind, heading east. Later we were strafed by 110s but our fighters appeared and shot down four of them. Again, we passed a most uncomfortable night not knowing the position of the Hun tanks but got back to Maddalena the next morning - 25th.”

“In order to ensure a full squadron strength of 12 aircraft, we would have one and sometimes two extra machines standing by, or taking off with the formation. If an aircraft turned back, the extra aircraft would take its place.Flying Officer Gibbes continued:

On the afternoon of the 22nd I foolishly volunteered to be the thirteenth man and when one aircraft turned back I took its place and became number two to Lin Knowles. I was to regret having made this stupid decision. The operation was to be an offensive patrol of the forward area by two squadrons, number 3 and 112, with 3 leading, led by Peter Jeffrey. We were escorting Wing Commander Freddie Rosier who was flying a Hurricane Mark 2. He wanted to get into Tobruk and it was planned that he would drop down there on the homeward leg of the patrol. Fred did not make Tobruk. We crossed the wire on Egypt’s boundary and climbed on a westerly heading weaving our way towards Bir el Gubi. Shortly after passing this landmark, and about to turn onto a northerly heading towards Tobruk, aircraft were seen and reported above our level, coming towards us. They passed about 3 or 4,000 feet above us on our port. Peter turned the wing to the left in a gentle turn behind the 20 plus 109s which climbed up into the sun and started to dive down and vigorously attack us. A fierce fight commenced. After a short time, the enemy started to form a circle about 2,000 feet above us, and they then started coming down in twos and threes from all directions.

After their attacks they would climb up again or sometimes, continue their dive through our formation and pull away before climbing up for further attacks. Ultimately, we ourselves somehow formed a defensive circle, when the lead aircraft caught up with the end machines. This circle was a recommended tactic and supposedly provided great protection to all aircraft in it. When enemy aircraft attacked, they would be subject to the firepower of one or more aeroplanes flying behind the machine being attacked. What a dreadful fallacy this theory really was. All it did with certainty, was to ensure that the leader was no longer recognisable, and virtually this made all aircraft leaderless. As the pairs were broken up by repeated attacks, we became a gaggle of single aircraft.

The Messerschmitts had the advantage of height and when they dived on us they proved to be difficult targets due to the great speed which they had built up in their dive. It was hard to get more than a fleeting shot at them as they flashed past.

One of our pilots, Wilfred Arthur, at the time a Flight Lieutenant, tried breaking upwards after each attack on him, meaning to play the Germans at their own game. He gained quite a lot of altitude before a number of the enemy made a concerted attack on him forcing him to make a hurried diving retreat back to us. From memory, I believe that one or two of our more twitchy pilots took a pot at him as he rejoined the circle. They had become used to seeing only enemy aircraft come down from above.

Eddie Jackson’s Tomahawk was hit by an explosive 20mm shell in the starboard wing root. A big section of the wing was blown off and it was quite amazing that the aircraft still flew. He remained aggressive and continued to use his aircraft to the full. This spoke well for the rugged construction of the Curtiss aircraft which was still able to take high G forces without the wing collapsing.

As I mentioned earlier, I was flying as Lin Knowles’s number 2. When the first attacks started, Lin pulled up to fire at a 109 which was diving onto our formation. I followed him up until a second 109 pulled in behind us. I called out a warning and broke out of its way. From then on I was not able to locate him again and indeed was kept too busy to really try. The intensity of the attacks was quite horrendous and we were all fully occupied in trying to stay alive and fighting back when possible.

At one stage I pulled up after a 109 which dived from south to north across the formation and I managed to get a full deflection shot at it. There was a vivid flash from his cockpit area on the starboard side, and the aircraft which had been climbing, fell off to starboard and started diving away. I felt that it had ‘had it’, but I was not able to watch further as I was myself attacked and by the time I got clear, there was nothing to be seen of my possible victim.

During the combat I fired at several aircraft but was unable to claim any results although I must have scored the odd hit. I only saw the definite strike. At one time I pulled up to have a shot at a 109 which was pulling away after an attack. I noticed a 109 shooting at me from extreme range, but he had to allow full deflection to hit me and as I didn't think he was laying off enough lead, I kept on with my attack on the escaping aircraft. I completely overlooked my diminishing speed and when near the stall, I was startled to hear the sound of bullets striking my aircraft and saw my starboard wing start to look like the family colander. In an agony of fear, I kicked on full left rudder and rammed the stick forward in a desperate attempt to get clear of the hail of bullets. The next moment, I was being thrown violently around the cockpit. I thought for a moment that my controls had been shot away but then realised that I was in an inverted spin. I thought of opening my canopy and releasing my harness and dropping clear, but as I had 4,000 feet I decided to stay with it and to see if I could regain control. Due to having my harness fairly loose, I had terrific difficulty in getting my feet onto the rudders. I was completely clear of the cockpit seat because of the outward inertia of the spin and my head was hard up against the canopy. By a supreme effort I manage to get on some opposite rudder and came out inverted. It was a simple matter to roll out. I tightened my harness. A short time later, while flying almost on the deck after diving out of the defensive circle to shoot at a 109, I pulled up fairly hard to rejoin my friends. I must have hit a slipstream as I flipped onto my back at about 300 feet above the desert. I had long practiced low aerobatics, but never this low. My reaction was automatic and I pushed the stick forward and rolled out. I was amazed to be still alive and I was shaking even more than before, if this was possible. Afterwards, one of the surviving pilots discussing the combat in the safety of the mess, said, ‘Did you see that bloke flick onto his back right on the deck and go in.’ So positive had he been of my fate that he hadn’t bothered to watch me actually hit. He was amazed when I finished the story for him.

A 109 carried out an attack on one of our aircraft and as it started pulling away and I was trying to get a shot at it, a Tomahawk dived from somewhere above with a lot of speed and firing from about a hundred yards, hit it cleanly in about the cockpit area. The Messerschmitt disintegrated in a ball of flames. As I watched the wings and bits falling down I could only admire such magnificent shooting. I think the Tomahawk was flown by Alan Rawlinson.

A 109 dived in to attack. A Tomahawk pulled up and carried out a head-on attack on it, both aircraft shooting furiously. Each held his attack until the last moment before breaking. They left it too long, clipped their starboard wings and each flew in a gentle but steepening dive away from each other to the desert below and hit almost simultaneously. A wing from each aircraft fluttered down almost together like falling leaves, hitting the ground about half way between the crashed aircraft. I watched and prayed that our pilot would bale out but he did not open his canopy, and was probably knocked out by the impact. The 109 pilot also went in with his aircraft. We later confirmed that the Tomahawk was flown by Lindsay Knowles.

The fight raged on and gradually we were forced lower and lower. Some of the lowest planes were literally skimming the desert. This gave some measure of relief as the 109s were no longer able to dive straight down through us and away. Instead they had to pull up after their attacks. Again, it stopped them diving as steeply which resulted in less speed and gave us a fraction more time to shoot at them as they flashed past. On the debit side, due to wind effect, our circle was gradually drifting to the south-east and this was carrying us over various German and Italian concentrations of troops, guns and tanks with a resulting hail of fire coming up at us from below to add to our worries. Some of the more aggressive pilots aimed an occasional burst at ground targets as they passed over, but I for one, was content to save my ammunition for use against the Luftwaffe. It seemed unlikely that any of us would survive, but I wanted to at least be able to shoot back until I was killed. The numbers of 109s would sometimes seem to dwindle, but just as we were starting to have some faint hope, a fresh batch would arrive, keen to be in at the kill. We were 150 miles from our base and they were a mere few miles from theirs. As they used up their supply of ammunition and petrol, they would land back, hurriedly re-arm, refuel and return to this combat.

Time passed and the fight went on. I looked at my watch, at my gauges and noting the way my petrol was diminishing, eased back my throttle a little, leaned my mixture as much as possible, probably more than I should have. Would my petrol last until darkness? If so, how far would we be able to fly before being forced to land, still miles inside enemy territory? Would we survive a landing in darkness away from an aerodrome? It would be unlikely.

At last the sun sank below the horizon and in the east a slight bluish tinge told of approaching night. There are fewer 109s now. There might be a hope, if only the leader would make a break for home. But where is the leader? Perhaps he is dead. Would it be possible for me to lead this team out of the circle where we were like a mob of sheep. I called up the CO. I called up Lin. Dead silence. I called up the mob and told them that I was going to make a break for home and broke away waggling my wings. Not a soul followed. I hurriedly rejoined the circle. The 109s looked as if they were leaving us. I called up again and again broke towards home waggling my wings. The circle broke almost to a man and followed. ’Woof’ Arthur flew up alongside me and took over the lead. It was a great relief to see him as I had doubts about my ability to find my way back to base. The little enemy dots were fading into the darkness.

Woof’s navigation was good and he led us into a newly captured aerodrome. We landed in approaching darkness, most of us very low in fuel and morale. The combat had lasted for one hour and five minutes. During this time we were under constant attack from above and for a fairly long period, from below as well.

I landed with only ten gallons of petrol left and I was practically right out of ammunition. The other pilots were also suffering from fuel shortage, and on reaching the aerodrome there was no pansy flying and of carrying out a normal circuit; no time to take precautions. Wheels went down and we went straight in praying that the runway was clear, and that we would be able to see the ground when the time came to hold off and put the aircraft down. A couple of the pilots had to make dead-stick landings when their motors cut on final and another had his motor cut when taxying in to disperse his aircraft.

We assembled, those who were left, at the mess tent of the squadron which had just moved up to this newly captured aerodrome. Word was passed to our squadron that we had landed. The relief of the squadron people must have been quite considerable, as only Alan Rawlinson had landed back and he had only been able to report having shot down two 109s (credited as one and one probable).

Word came through that Peter Jeffrey was safe but that Freddie Rosier was missing. Fred was not seen after the fight started. Also missing from the operation were Lin Knowles, Sammy Lees, Robbie Roberts, Ron Simes and Bill Kloster. Peter had been the sixth pilot missing. Sammy Lees and Lin Knowles were later confirmed to have been killed and Bill Kloster and Robbie Roberts had become prisoners of war. Ron Simes walked back.

When the combat started, Fred Rosier was flying just below the Tomahawks in his Hurricane. He tried to keep up with the climbing squadrons but his machine was not capable of doing so. He saw one of the Tomahawks get shot down and the pilot land and get out of his aircraft. As he couldn't get up to the fight and as this pilot was miles behind enemy lines, he decided to do the next best thing and pick him up.

“22 November 1941 proved to be a day of disaster for 3 Squadron. By dusk our pilot strength had been depleted by almost 50%. In the morning battle we lost three pilots, all killed, and in the afternoon, a further four, two of whom were killed and the other two became prisoners of war. Al Rawlinson had been the only pilot of our 11 to land back at base. A further five surviving pilots had landed at a forward aerodrome, and two others arrived back the following day.Totally the two Tomahawk squadrons five Bf 109s destroyed, one probable and eight damaged for the loss of eight fighters (seven Tomahawks and one Hurricane) and several others damaged.

My morale was at bedrock and I thought that I would not be able to take it anymore, and I spent the whole (next) morning mooching around in a state of funk and dreaded bring asked to fly again. I was ashamed of my fear and frightened that my friends might see it. I kept to myself as much as possible, but occasionally I would go to the operations tent, pretending that I wanted to have another go at the Huns, but frightened that if I was given a job I would not be able to force myself into getting into my aeroplane. It would have to be a new aircraft too. My aircraft was in the workshops and would be there for quite a while being patched up.”

Between 08:20 and 08:30 on 30 November, six MC.200s of the 153o Gruppo, five G.50bis of the 378a Squadriglia, 155o and three G.50bis from the 20o Gruppo took off to escort 18 Ju 87s of II/StG 2 out to attack troops of the New Zealand Division. Bf 109s from II/JG 27 was also involved in escorting this mission as top cover. The formation of Ju 87s proceeded to the target in Bir el Gobi in a column, with the G.50bis of the 155o Gruppo on their right in line abreast.

En route to the target they were intercepted by a reportedly five Hurricanes or P-40s. The attack was interrupted by the prompt intervention of the Bf 109s and Oberfeldwebel Otto Schulz of 4./JG 27 claimed two P-40s; one at 09:10 north-east of Bir el Gobi and a second at 09:20 south-west of El Adem.

The Stukas reached the target at 09:10 and here an indefinite number of enemy fighters engaged all the escorting fighters and the combat continued during the return flight. Totally the returning Italian pilots claimed five destroyed, two probable and two damaged. Tenente Colonnello Luigi Bianchi (155o Gruppo) attacked some fighters attacking the rear of the Stukas and he returned claiming one Hurricane shot down and a probable Tomahawk having used 260 rounds of ammunition. Segente Italo Abraim (378a Squadriglia) claimed a destroyed Tomahawk (using only 12 rounds of ammunition!). Tenente Tulio Martinelli, Tenente Giuseppe Bonfiglio and Tenente Vittorio Galfetti (all 378a Squadriglia) returned claiming two shared damaged. Sottotenente Giorgio Oberwerger (352a Squadriglia, 20o Gruppo) and Sottotenente Pietro Zanello (352a Squadriglia, 20o Gruppo) claimed one Tomahawk each while Maresciallo Egeo Pardi (374a Squadriglia, 153o Gruppo) claimed one and one probable Tomahawk. Two G.50s from the 378a Squadriglia were shot down; Sottotenente Eugenio Giunta (MM5967) PoW and Sergente Girolamo Monaldi (MM6023) KIA. The 374a Squadriglia suffered two damaged MC.200s with both pilots wounded (Maresciallo Egeo Pardi and Tenente Mario Mauro) while a third MC.200 from 153o Gruppo, hit in the fuel tank, force-landed near Umm er Rzem. Two more MC.200s returned to base slightly damaged.

They had been in combat with Tomahawks from 112 and 3 RAAF Squadrons which had taken off together for a sweep.

112 Squadron reported that they took off at 08:30 with 12 Tomahawks and joining up with an equal number from 3 RAAF Squadron in an offensive wing sweep over the El Adem area, the wing being led by Wing Commander Peter Jeffrey DFC. They intercepted a force of 35-40 enemy machines in several layers, 15 Ju 87s at 6,000ft, 20 G.50s and MC.200s from 7,000-8,000ft and five Bf 109s as top cover. Wing Commander Jeffrey detailed one section from 112 Squadron to watch the Messerschmitts and the remainder of the squadron, with 3 RAAF Squadron, to concentrate on the middle and lower formations. The Stukas jettisoned their bombs and in the combat, one MC.200 and two G.50s were claimed destroyed by 112 Squadron with one Bf 109 and one G.50 damaged. One of the G.50s were shot down by Sergeant 'Rudy' Leu (AK509) after a stern attack while a G.50 was claimed damaged by Pilot Officer ‘Ken’ Sands. Pilot Officer Neville Bowker (AN338) claimed one MC.200 destroyed, but he was then shot down by a G.50 and was forced to crash-land on the outskirts of LG 122, his machine being badly damaged. Pilot Officer Neville Duke (AK402/F) chased a G.50 for a long way before finally shooting it down. Two or three Bf 109s and a G.50 or MC.200 then attacked from him astern. He turned and gave one of the Bf 109s a short burst, which appeared to have damaged it. He was followed home by another Bf 109F and was hit in the port wing and main petrol tank. His machine went over onto its back at about 500ft and hit the ground on its belly just as he pulled it round. The aircraft took to the air again with a burst of power and crash-landed. Duke leapt out and had only just cleared the aircraft and hidden himself in the scrub when it was strafed and set on fire. Later he was picked up by a Lysander and returned to base. His victor seems to have been Oberfeldwebel Otto Schulz of 4./JG 27 whose habit was to strafe downed aircraft for good measure.

3 RAAF Squadron reported that 12 Tomahawks took off at 08:40 and joined 112 Squadron in an offensive wing sweep over the El Adem area, the wing being led by Wing Commander Jeffrey DFC. Australian pilots taking part were Sergeant 'Tiny' Cameron (AK506), Flying Officer Robert Gibbes (AN499), Sergeant Derek Scott (AN374), Squadron Leader Rawlinson (AN408), Flight Lieutenant Wilfred Arthur (AN224), Flying Officer Louis Spence (AN457), Sergeant Frank Blunden Reid (AM406), Flying Officer Thomas Trimble (AM384), Sergeant Rex Wilson (AM392), Pilot Officer Eggleston (AN336), Sergeant 'Wal' Mailey (AK446) and Pilot Officer 'Nicky' Barr (AM378). Pilot Officer Barr returned at 09:00 with engine trouble. The patrol intercepted reportedly between 40 and 50 enemy aircraft and in the ensuing combat they claimed 13 destroyed and 18 damaged. Squadron Leader Rawlinson landed back at 09:40 claiming one MC.200 destroyed. Flying Officer Spence followed him. Sergeant Wilson landed with wheels up just off the aerodrome at 09:45 with landing gears unserviceable, and oil running everywhere. He claimed one MC.200, one Ju 87 and one Bf 109 damaged. At 09:55, Flying Officer Trimble, Sergeant Reid and Sergeant Mailey landed. Trimble claimed two MC.200s destroyed and three Ju 87s damaged, Reid claimed three damaged Ju 87s while Mailey claimed one MC.200 and one G.50 destroyed and three damaged Ju 87s. Pilot Officer Eggleston landed at 10:05. At 10:10, Flying Officer Gibbes and Sergeant Scott landed. Gibbes claimed one G.50 destroyed and one Bf 109 damaged and Scott claimed one G.50 and one Ju 87 destroyed and one Ju 87 damaged. Finally, at 10:15, Wing Commander Jeffrey landed sitting well up in the cockpit - he had landed alongside Sergeant Cameron and picked him up in the desert. Sergeant Cameron who after having claimed one G.50 destroyed and four Ju 87s damaged had been shot down and forced to baled out. From this operation Flight Lieutenant Arthur failed to return but he returned to the Squadron at 17:00 in a borrowed Hurricane. He had been forced to land inside the Tobruk fortress when his distributor became unserviceable. He had had a field day claiming two Ju 87s, one G.50 and one MC.200 destroyed.

No Ju 87s were lost in this combat but two from 4./St.G 2 returned with wounded gunners (Unteroffizier Otto Herbert and Gefreiter Manfred Spiegelberg).

Awarded a Bar to his DFC on 11 December, he was attached to HQ, Middle East, to form the Air Fighting School, Egypt. He commanded this unit in January and February 1942.

Returning to Australia during 1942, he assisted in forming a fighter OTU, becoming CFI at Mildura.

In 1943, he was promoted to Squadron Commander and Wing Leader. From 26 April 1943, he formed and commanded 79 RAAF Squadron on Spitfire Mk.Vcs, leading this unit to New Guinea, Goodenough, and Kiriwina Islands.

In 1944, he commanded the Parachute Training Unit, which supported the formation of the Australian Parachute Battalion and the training to the Z Special Forces. He took over command of 78 (Fighter) Wing at Tarakan, Borneo, in May 1945, returning to Australia in December 1945.

Rawlinson ended the war with 1 probable biplane victory and a total of 8 destroyed.

He then took up a Permanent Commission in the RAF in the UK in 1948 as an Squadron Leader. In the UK, he spent a short spell at HQ, Fighter Command, and was then posted to command 54 Squadron at Odiham in 1949 with Vampires, then becoming Wing Commander Flying there. Awarded an AFC, he served briefly at Southern Sector and then commanded RAF Filton, leading a Wing comprised of 501 and 614 RAuxAF Squadrons. Later in 1953 he formed and commanded the UK's first Guided Weapons Trials Unit, testing beam-riding missiles for the Meteor NF11 in Wales, and then at Woomera, Australia. He flew as a GW Test Pilot with the contractors, Fairey Aviation, using pilotless Fireflies and then Jindivik drones as targets.

He received an OBE in 1958, and later became Master Controller at Patrington, introducing procedures to integrate Surface to Air Weapons with fighters.

In 1960, he commanded RAF Buchan Sector in Scotland, but in 1961 elected to retire as a Group Captain, and returned to Australia.

During his flying career, he flew some 53 different types of aircraft, from bi-planes to supersonic jets.

He lived in retirement in Crafers, South Australia.

Rawlinson passed away on 28 August 2007.

Claims:

| Kill no. | Date | Time | Number | Type | Result | Plane type | Serial no. | Locality | Unit |

| 1940 | |||||||||

| 19/11/40 | 1 | CR.42 (a) | Damaged | Gladiator II | L9044 | 7m E Rabia | 3 RAAF Squadron | ||

| 26/12/40 | 14:05 | 1 | CR.42 (b) | Probable | Gladiator II | N5782 | NE Sollum Bay | 3 RAAF Squadron | |

| 1941 | |||||||||

| 25/01/41 | 07:30-08:45 | 1 | G.50 (c) | Damaged | Gladiator I | K7963 | 13km SE Mechili | 3 RAAF Squadron | |

| 25/01/41 | 07:30-08:45 | 1 | G.50 (c) | Damaged | Gladiator I | K7963 | 13km SE Mechili | 3 RAAF Squadron | |

| 1 | 03/04/41 | 13:00 | 1 | Ju 87 (d) | Destroyed | Hurricane I | V7772 | Sceledeina area | 3 RAAF Squadron |

| 2 | 03/04/41 | 13:00 | 1 | Ju 87 (d) | Destroyed | Hurricane I | V7772 | Sceledeina area | 3 RAAF Squadron |

| 03/04/41 | 13:00 | 1 | Ju 87 (d) | Probable | Hurricane I | V7772 | Sceledeina area | 3 RAAF Squadron | |

| 03/04/41 | 13:00 | 1 | Ju 87 (d) | Damaged | Hurricane I | V7772 | Sceledeina area | 3 RAAF Squadron | |

| 07/04/41 | 14:05- | 1 | Ju 52/3m (e) | Destroyed on the ground | Hurricane I | 10m S Mechili | 3 RAAF Squadron | ||

| 19/06/41 | 1 | Martin M-167 (f) | Damaged | Tomahawk IIb | AK388 | Jezzine | 3 RAAF Squadron | ||

| 19/06/41 | 1 | Martin M-167 (f) | Damaged | Tomahawk IIb | AK388 | Jezzine | 3 RAAF Squadron | ||

| 3 | 28/06/41 | 1 | Martin M-167 (g) | Destroyed | Tomahawk IIb | AK446 | Palmyra | 3 RAAF Squadron | |

| 4 | 28/06/41 | 1 | Martin M-167 (g) | Destroyed | Tomahawk IIb | AK446 | Palmyra | 3 RAAF Squadron | |

| 5 | 28/06/41 | 1 | Martin M-167 (g) | Destroyed | Tomahawk IIb | AK446 | Palmyra | 3 RAAF Squadron | |

| 22/11/41 | 09:45-11:10 | 1 | Bf 109F (h) | Damaged | Tomahawk IIb | AN408 | Bir El Gobi | 3 RAAF Squadron | |

| 6 | 22/11/41 | 16:15-17:15 | 1 | Bf 109F (i) | Destroyed | Tomahawk IIb | AN365 | SE El Adem | 3 RAAF Squadron |

| 7 | 22/11/41 | 16:15-17:15 | 1 | Bf 109F (i) | Destroyed | Tomahawk IIb | AN365 | SE El Adem | 3 RAAF Squadron |

| 22/11/41 | 16:15-17:15 | 1 | Bf 109F (i) | Damaged | Tomahawk IIb | AN365 | SE El Adem | 3 RAAF Squadron | |

| 22/11/41 | 1 | Bf 109F (j) | Damaged | Tomahawk IIb | AN365 | SE El Adem | 3 RAAF Squadron | ||

| 8 | 30/11/41 | 09:15 | 1 | MC.200 (k) | Destroyed | Tomahawk IIb | AN408 | El Adem area | 3 RAAF Squadron |

Biplane victories: 1 probable, 3 damaged.

TOTAL: 8 destroyed, 2 probable, 9 damaged, 1 destroyed on the ground.

(a) Claimed in combat with the 82a Squadriglia, 13o Gruppo, which claimed six shared Gladiators and one damaged while suffering four lightly damaged fighters. 3 RAAF Squadron claimed four CR.42s, one probable and two damaged while losing one Gladiator and getting one damaged.